Recommended for Startup Investors?

Yes

Why

AI research and computer science PhD Kai-Fu Lee who rode every wave of the 90's and 00's (head of Google China, Apple voice recognition during Sculley's era, and Microsoft China/Asia Research,) breaks down what AI is, what AI businesses need to thrive, and what the criteria for dominance in the 21st century will look like.

My Notes By Chapter

- (1) China's Sputnik moment

- In March 2016 when AlphaGo beat Lee Sedol in Go, 280mm Chinese viewers turned in to watch.

- "This pattern-finding process is easier when the data is labeled with that desired outcome—"cat" versus "no cat"; "clicked" versus "didn't click"; "won game" versus "lost game."

- Deep learning is what’s known as “narrow AI”—intelligence that takes data from one specific domain and applies it to optimizing one specific outcome. While impressive, it is still a far cry from “general AI,” the all-purpose technology that can do everything a human can.

- "The only way to survive this battle is to constantly improve one’s product but also to innovate on your business model and build a “moat” around your company. If one’s only edge is a single novel idea, that idea will invariably be copied, your key employees will be poached, and you’ll be driven out of business by VC-subsidized competitors. This rough-and-tumble environment makes a strong contrast to Silicon Valley, where copying is stigmatized and many companies are allowed to coast on the basis of one original idea or lucky break. That lack of competition can lead to a certain level of complacency, with entrepreneurs failing to explore all the possible iterations of their first innovation. The messy markets and dirty tricks of China’s “copycat” era produced some questionable companies, but they also incubated a generation of the world’s most nimble, savvy, and nose-to-the-grindstone entrepreneurs. These entrepreneurs will be the secret sauce that helps China become the first country to cash in on AI’s age of implementation.

- Until about five years ago, it made sense to directly compare the progress of Chinese and U.S. internet companies as one would describe a race. They were on roughly parallel tracks, and the United States was slightly ahead of China. But around 2013, China’s internet took a right turn. Rather than following in the footsteps or outright copying of American companies, Chinese entrepreneurs began developing products and services with simply no analog in Silicon Valley. Analysts describing China used to invoke simple Silicon Valley–based analogies when describing Chinese companies—“the Facebook of China,” “the Twitter of China”—but in the last few years, in many cases these labels stopped making sense. The Chinese internet had morphed into an alternate universe.

- These recent and powerful developments naturally tilt the balance of power in China’s direction. But on top of this natural rebalancing, China’s government is also doing everything it can to tip the scales. The Chinese government’s sweeping plan for becoming an AI superpower pledged widespread support and funding for AI research, but most of all it acted as a beacon to local governments throughout the country to follow suit. Chinese governance structures are more complex than most Americans assume; the central government does not simply issue commands that are instantly implemented throughout the nation. But it does have the ability to pick out certain long-term goals and mobilize epic resources to push in that direction. The country’s lightning-paced development of a sprawling high-speed rail network serves as a living example.

- Local government leaders responded to the AI surge as though they had just heard the starting pistol for a race, fully competing with each other to lure AI companies and entrepreneurs to their regions with generous promises of subsidies and preferential policies. That race is just getting started, and exactly how much impact it will have on China’s AI development is still unclear. But whatever the outcome, it stands in sharp contrast to a U.S. government that deliberately takes a hands-off approach to entrepreneurship and is actively slashing funding for basic research.

- This new AI world order will be particularly jolting to Americans who have grown accustomed to a near-total dominance of the technological sphere. For as far back as many of us can remember, it was American technology companies that were pushing their products and their values on users around the globe. As a result, American companies, citizens, and politicians have forgotten what it feels like to be on the receiving end of these exchanges, a process that often feels akin to “technological colonization.” China does not intend to use its advantage in the AI era as a platform for such colonization, but AI-induced disruptions to the political and economic order will lead to a major shift in how all countries experience the phenomenon of digital globalization.

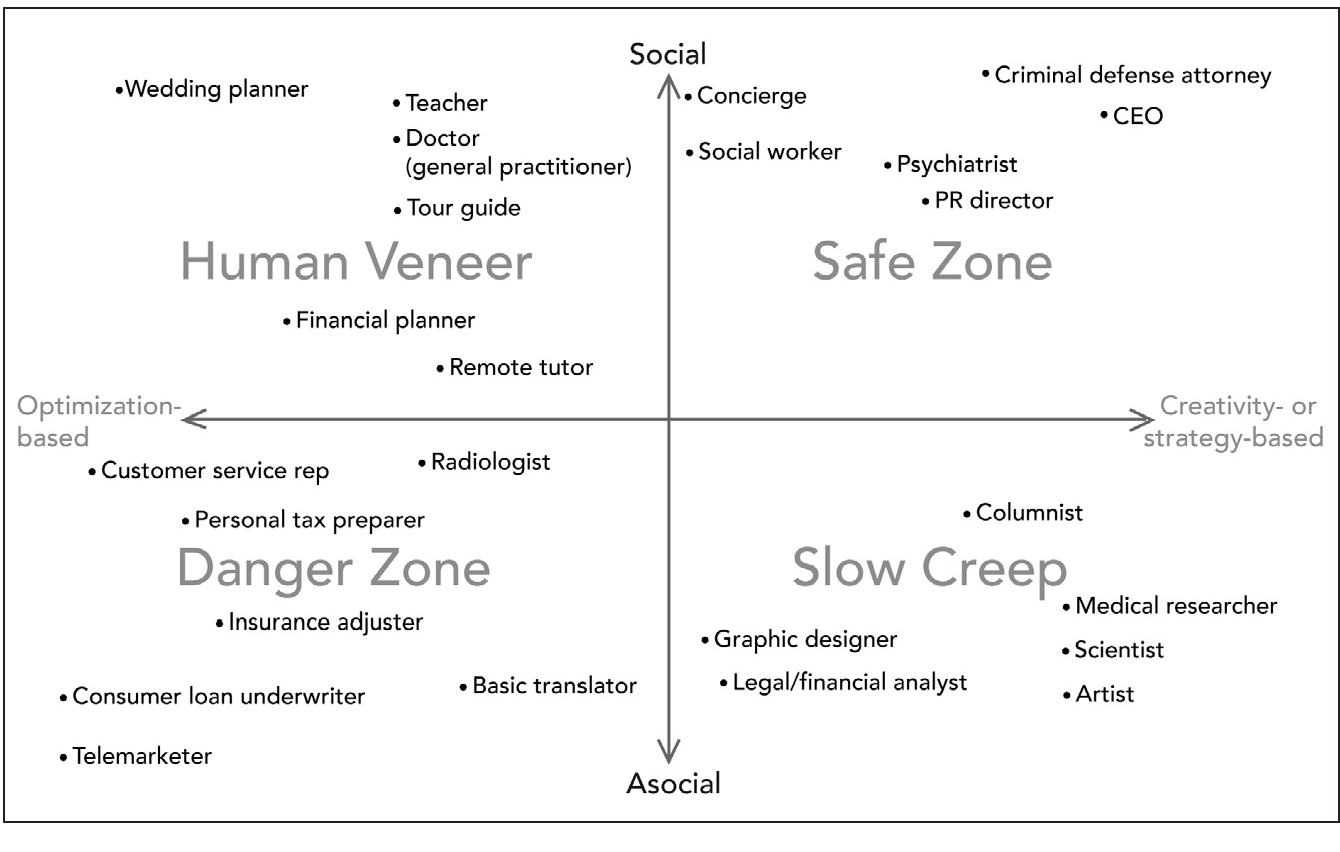

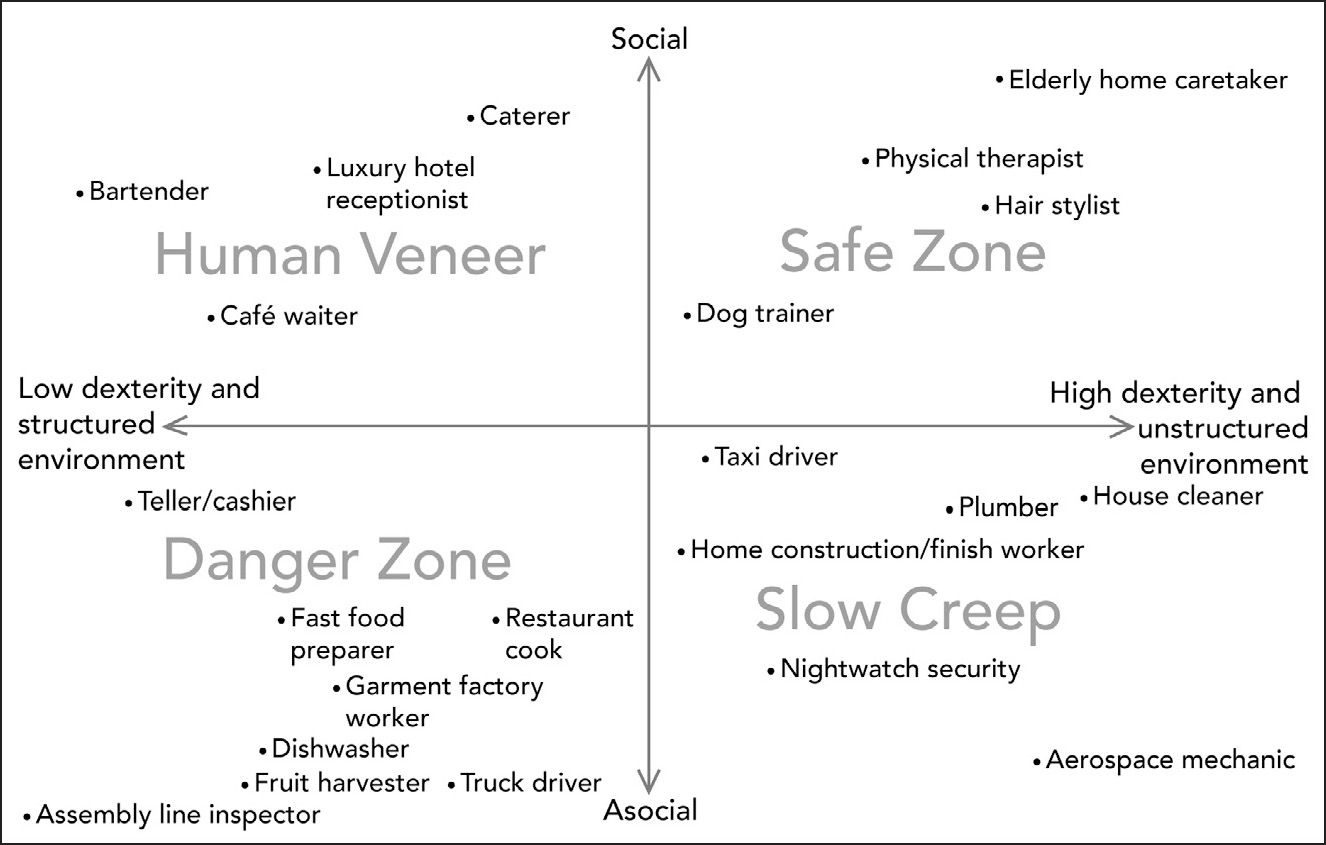

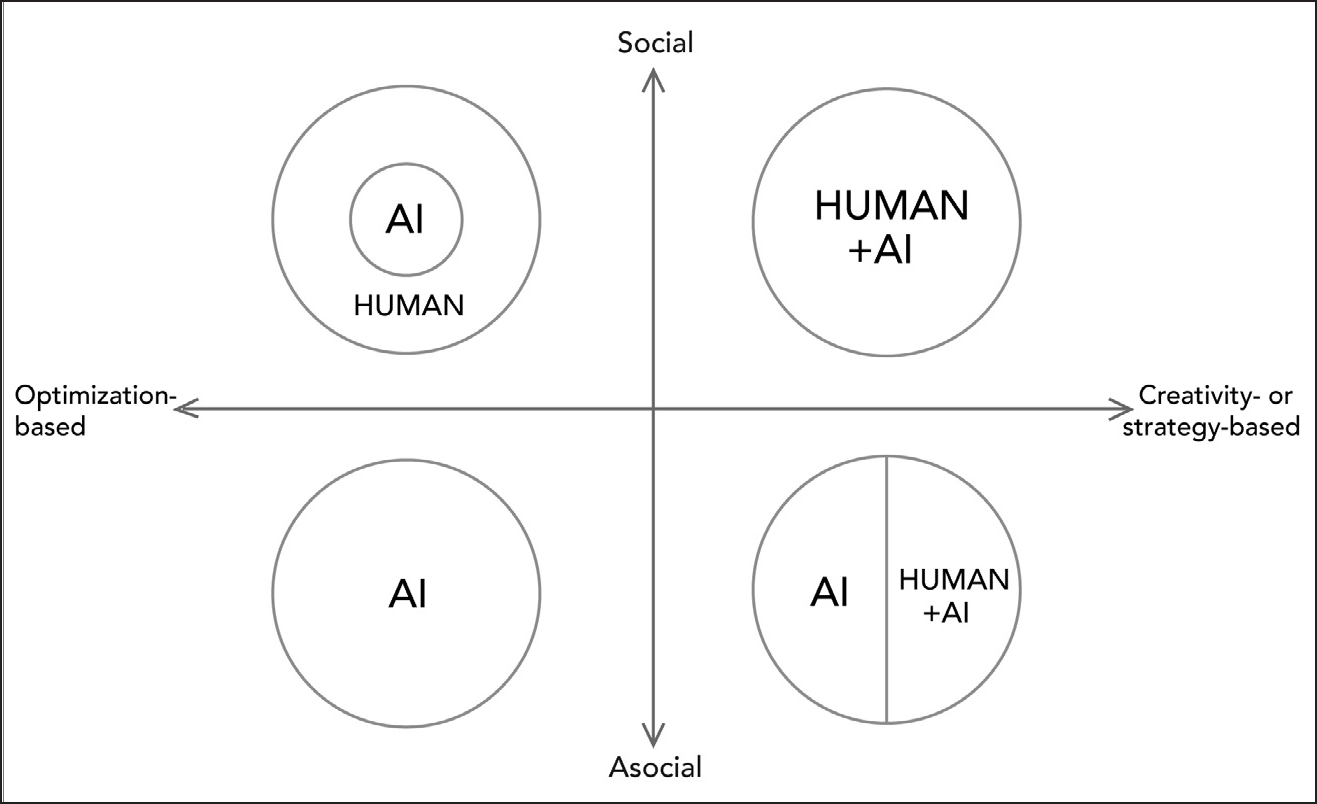

- Human civilization has in the past absorbed similar technology-driven shocks to the economy, turning hundreds of millions of farmers into factory workers over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But none of these changes ever arrived as quickly as AI. Based on the current trends in technology advancement and adoption, I predict that within fifteen years, artificial intelligence will technically be able to replace around 40 to 50 percent of jobs in the United States. Actual job losses may end up lagging those technical capabilities by an additional decade, but I forecast that the disruption to job markets will be very real, very large, and coming soon.

- At the same time, AI-driven automation in factories will undercut the one economic advantage developing countries historically possessed: cheap labor. Robot-operated factories will likely relocate to be closer to their customers in large markets, pulling away the ladder that developing countries like China and the “Asian Tigers” of South Korea and Singapore climbed up on their way to becoming high-income, technology-driven economies. The gap between the global haves and have-nots will widen, with no known path toward closing it. The AI world order will combine winner-take-all economics with an unprecedented concentration of wealth in the hands of a few companies in China and the United States. The AI world order will combine winner-take-all economics with an unprecedented concentration of wealth in the hands of a few companies in China and the United States. This, I believe, is the real underlying threat posed by artificial intelligence: tremendous social disorder and political collapse stemming from widespread unemployment and gaping inequality.

- 2. Copycats in the Museum: Xiaonei was a hit, but one that Wang sold off too early. As the site grew rapidly, he couldn’t raise enough money to pay for server costs and was forced to accept a buyout. Under new ownership, a rebranded version of Xiaonei—now called Renren, “Everybody”—eventually raised $740 million during its 2011 debut on the New York Stock Exchange. In 2007, Wang was back at it again, making a precise copy of the newly founded Twitter. The clone was done so well that if you changed the language and the URL, users could easily be fooled into thinking they were on the original Twitter. The Chinese site, Fanfou, thrived for a moment but was soon shut down over politically sensitive content. Then, three years later Wang took the business model of red-hot Groupon and turned it into the Chinese group-buying site Meituan.

- In the end, it was Wang who would get the last laugh. By late 2017, Groupon’s market cap had shriveled to $2.58 billion, with its stock trading at under one-fifth the price of its 2011 initial public offering (IPO). The former darling of the American startup world had been stagnant for years and slow to react when the group-buying craze faded. Meanwhile, Wang Xing’s Meituan had triumphed in a brutally competitive environment, beating out thousands of similar group-buying websites to dominate the field. It then branched out into dozens of new lines of business. It is now the fourth most valuable startup in the world, valued at $30 billion, and Wang sees Alibaba and Amazon as his main competitors going forward.

- In creating his early clones of Facebook and Twitter, Wang was in fact relying entirely on the Silicon Valley playbook. This first phase of the copycat era—Chinese startups cloning Silicon Valley websites—helped build up baseline engineering and digital entrepreneurship skills that were totally absent in China at the time. But it was a second phase—Chinese startups taking inspiration from an American business model and then fiercely competing against each other to adapt and optimize that model specifically for Chinese users—that turned Wang Xing into a world-class entrepreneur. Wang didn’t build a $30 billion company by simply bringing the group-buying business model to China. Over five thousand companies did the exact same thing, including Groupon itself. The American company even gave itself a major leg up on local copycats by partnering with a leading Chinese internet portal. Between 2010 and 2013, Groupon and its local impersonators waged an all-out war for market share and customer loyalty, burning billions of dollars and stopping at nothing to slay the competition.

- Corporate America is unprepared for this global wave of Chinese entrepreneurship because it fundamentally misunderstood the secret to The Cloner’s success. Wang Xing didn’t succeed because he’d been a copycat. He triumphed because he’d become a gladiator. [Contrasting Cultures] Startups and the entrepreneurs who found them are not born in a vacuum. Their business models, products, and core values constitute an expression of the unique cultural time and place in which they come of age.

- Silicon Valley’s and China’s internet ecosystems grew out of very different cultural soil. Entrepreneurs in the valley are often the children of successful professionals, such as computer scientists, dentists, engineers, and academics. Growing up they were constantly told that they—yes, they in particular—could change the world. Their undergraduate years were spent learning the art of coding from the world’s leading researchers but also basking in the philosophical debates of a liberal arts education. When they arrived in Silicon Valley, their commutes to and from work took them through the gently curving, tree-lined streets of suburban California.

- It’s an environment of abundance that lends itself to lofty thinking, to envisioning elegant technical solutions to abstract problems. Throw in the valley’s rich history of computer science breakthroughs, and you’ve set the stage for the geeky-hippie hybrid ideology that has long defined Silicon Valley. Central to that ideology is a wide-eyed techno-optimism, a belief that every person and company can truly change the world through innovative thinking. Copying ideas or product features is frowned upon as a betrayal of the zeitgeist and an act that is beneath the moral code of a true entrepreneur. It’s all about “pure” innovation, creating a totally original product that generates what Steve Jobs called a “dent in the universe.”

- In stark contrast, China’s startup culture is the yin to Silicon Valley’s yang: instead of being mission-driven, Chinese companies are first and foremost market-driven. Their ultimate goal is to make money, and they’re willing to create any product, adopt any model, or go into any business that will accomplish that objective. That mentality leads to incredible flexibility in business models and execution, a perfect distillation of the “lean startup” model often praised in Silicon Valley. It doesn’t matter where an idea came from or who came up with it. All that matters is whether you can execute it to make a financial profit. The core motivation for China’s market-driven entrepreneurs is not fame, glory, or changing the world. Those things are all nice side benefits, but the grand prize is getting rich, and it doesn’t matter how you get there.

- Jarring as that mercenary attitude is to many Americans, the Chinese approach has deep historical and cultural roots. Rote memorization formed the core of Chinese education for millennia. Entry into the country’s imperial bureaucracy depended on word-for-word memorization of ancient texts and the ability to construct a perfect “eight-legged essay” (八股散文) following rigid stylistic guidelines. While Socrates encouraged his students to seek truth by questioning everything, ancient Chinese philosophers counseled people to follow the rituals of sages from the ancient past. Rigorous copying of perfection was seen as the route to true mastery.

- Layered atop this cultural propensity for imitation is the deeply ingrained scarcity mentality of twentieth-century China. Most Chinese tech entrepreneurs are at most one generation away from grinding poverty that stretches back centuries. Many are only children—products of the now-defunct “One Child Policy”—carrying on their backs the expectations of two parents and four grandparents who have invested all their hopes for a better life in this child. Growing up, their parents didn’t talk to them about changing the world. Rather, they talked about survival, about a responsibility to earn money so they can take care of their parents when their parents are too old to work in the fields. A college education was seen as the key to escaping generations of grinding poverty, and that required tens of thousands of hours of rote memorization in preparing for China’s notoriously competitive entrance exam. During these entrepreneurs’ lifetimes, China wrenched itself out of poverty through bold policies and hard work, trading meal tickets for paychecks for equity stakes in startups.

- Combine these three currents—a cultural acceptance of copying, a scarcity mentality, and the willingness to dive into any promising new industry—and you have the psychological foundations of China’s internet ecosystem.

- This is not meant to preach a gospel of cultural determinism. As someone who has moved between these two countries and cultures, I know that birthplace and heritage are not the sole determinants of behavior. Personal eccentricities and government regulation are hugely important in shaping company behavior. In Beijing, entrepreneurs often joke that Facebook is “the most Chinese company in Silicon Valley” for its willingness to copy from other startups and for Zuckerberg’s fiercely competitive streak. Likewise, while working at Microsoft, I saw how government antitrust policy can defang a wolf-like company. But history and culture do matter, and in comparing the evolution of Silicon Valley and Chinese technology, it’s crucial to grasp how different cultural melting pots produced different types of companies.

- For years, the copycat products that emerged from China’s cultural stew were widely mocked by the Silicon Valley elite. They were derided as cheap knockoffs, embarrassments to their creators and unworthy of the attention of true innovators. But those outsiders missed what was brewing beneath the surface. The most valuable product to come out of China’s copycat era wasn’t a product at all: it was the entrepreneurs themselves.

- But after a meeting with Yahoo! founder Jerry Yang, Zhang switched his focus to creating a Chinese-language search engine and portal website. He named his new company Sohoo, a not-so-subtle mashup of the Chinese word for “search” (sou) ) and the company’s American role model. He soon switched the spelling to “Sohu” to downplay the connection, but this kind of imitation was seen as more flattery than threat to the American web juggernaut. At the time, Silicon Valley saw the Chinese internet as a novelty, an interesting little experiment in a technologically backward country.

- The storm continued to rage on, all while our (Google China) team kept failing to find or locate the offending ads from the television program. Later that night I received an excited email from one of our engineers. He had figured out why we couldn’t reproduce the results: because the search engine shown on the program wasn’t Google. It was a Chinese copycat search engine that had made a perfect copy of Google—the layout, the fonts, the feel—almost down to the pixel. The site’s search results and ads were their own but had been packaged online to be indistinguishable from Google China. The engineer had noticed just one tiny difference, a slight variation in the color of one font used. The impersonators had done such a good job that all but one of Google China’s seven hundred employees watching onscreen had failed to tell them apart.

- Silicon Valley investors take as an article of faith that a pure innovation mentality is the foundation on which companies like Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple are built. It was an irrepressible impulse to “think different” that drove people like Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg, and Jeff Bezos to create these companies that would change the world. In that school of thought, China’s knockoff clockmakers were headed down a dead-end road. A copycat mentality is a core stumbling block on the path to true innovation. By blindly imitating others—or so the theory goes—you stunt your own imagination and kill the chances of creating an original and innovative product.

- But I saw early copycats like Wang Xing’s Twitter knockoff not as stumbling blocks but as building blocks. That first act of copying didn’t turn into an anti-innovation mentality that its creator could never shake. It was a necessary steppingstone on the way to more original and locally tailored technology products. The engineering know-how and design sensibility needed to create a world-class technology product don’t just appear out of nowhere. In the United States, universities, companies, and engineers have been cultivating and passing down these skillsets for generations. Each generation has its breakout companies or products, but these innovations rest on a foundation of education, mentorship, internships, and inspiration.

- China had no such luxury. When Bill Gates founded Microsoft in 1975, China was still in the throes of the Cultural Revolution, a time of massive social upheaval and anti-intellectual fever. When Sergei Brin and Larry Page founded Google in 1998, just 0.2 percent of the Chinese population was connected to the internet, compared with 30 percent in the United States. Early Chinese tech entrepreneurs looking for mentors or model companies within their own country simply couldn’t find them. So instead they looked abroad and copied them as best they could.

- It was a crude process to be sure, and sometimes an embarrassing one. But it taught these copycats the basics of user interface design, website architecture, and back-end software development. As their clone-like products went live, these market-driven entrepreneurs were forced to grapple with user satisfaction and iterative product development. If they wanted to win the market, they had to beat not just their Silicon Valley inspiration but also droves of similar copycats. They learned what worked and what didn’t with Chinese users. They began to iterate, improve, and localize the product to better serve their customers.

- As a result, when Chinese copycats went head-to-head with their Silicon Valley forefathers, they took that American unwillingness to adapt and weaponized it. Every divergence between Chinese user preferences and a global product became an opening that local competitors could attack. They began tailoring their products and business models to local needs, and driving a wedge between Chinese internet users and Silicon Valley.

- "Free is Not a Business Model" (eBay condescendingly lecturing Ma)

- But Ma’s greatest weapon was his deployment of a “freemium” revenue model, the practice of keeping basic functions free while charging for premium services. At the time, eBay charged sellers a fee just to list their products, another fee when the products were sold, and a final fee if eBay-owned PayPal was used for payment. Conventional wisdom held that auction sites or e-commerce marketplace sites needed to do this in order to guarantee steady revenue streams.

- But as competition with eBay heated up, Ma developed a new approach: he pledged to make all listings and transactions on Taobao free for the next three years, a promise he soon extended indefinitely. It was an ingenious PR move and a savvy business play. In the short term, it won goodwill from Chinese sellers still leery of internet transactions. Allowing them to list for free helped Ma build a thriving marketplace in a low-trust society. It took years to get there, but in the long term, that marketplace grew so large that in order to get their products noticed, power sellers had to pay Ma for advertisements and higher search rankings. Brands would end up paying even larger premiums to list on Taobao’s more high-end sister site, Tmall.

- eBay bungled its response. In a condescending press release, the company lectured Ma, claiming “free is not a business model."

- The American users’ maps show a tight clustering of green and yellow in the upper left corner where the top search results appeared, with a couple of red dots for clicks on the top two results. American users remain on the page for around ten seconds before navigating away. In contrast, Chinese users’ heat maps look like a hot mess. The upper left corner has the greatest cluster of glances and clicks, but the rest of the page is blanketed in smudges of green and specks of red. Chinese users spent between thirty and sixty seconds on the search page, their eyes darting around almost all the results as they clicked promiscuously.

- Eye-tracking maps revealed a deeper truth about the way both sets of users approached search. Americans treated search engines like the Yellow Pages, a tool for simply finding a specific piece of information. Chinese users treated search engines like a shopping mall, a place to check out a variety of goods, try each one on, and eventually pick a few things to buy. For tens of millions of Chinese new to the internet, this was their first exposure to such a variety of information, and they wanted to sample it all.

- As a succession of American juggernauts—eBay, Google, Uber, Airbnb, LinkedIn, Amazon—tried and failed to win the Chinese market, Western analysts were quick to chalk up their failures to Chinese government controls. They assumed that the only reason Chinese companies survived was due to government protectionism that hobbled their American opponents.

- In my years of experience working for those American companies and now investing in their Chinese competitors, I’ve found Silicon Valley’s approach to China to be a far more important reason for their failure. American companies treat China like just any other market to check off their global list. They don’t invest the resources, have the patience, or give their Chinese teams the flexibility needed to compete with China’s world-class entrepreneurs. They see the primary job in China as marketing their existing products to Chinese users. In reality, they need to put in real work tailoring their products for Chinese users or building new products from the ground up to meet market demands. Resistance to localization slows down product iteration and makes local teams feel like cogs in a clunky machine.

- Silicon Valley companies also lose out on top talent. With so much opportunity now for growth within Chinese startups, the most ambitious young people join or start local companies. They know that if they join the Chinese team of an American company, that company’s management will forever see them as “local hires,” workers whose utility is limited to their country of birth. They’ll never be given a chance to climb the hierarchy at the Silicon Valley headquarters, instead bumping up against the ceiling of a “country manager” for China. The most ambitious young people—the ones who want to make a global impact—chafe at those restrictions, choosing to start their own companies or to climb the ranks at one of China’s tech juggernauts. Foreign firms are often left with mild-mannered managers or career salespeople helicoptered in from other countries, people who are more concerned with protecting their salary and stock options than with truly fighting to win the Chinese market. Put those relatively cautious managers up against gladiatorial entrepreneurs who cut their teeth in China’s competitive coliseum, and it’s always the gladiators who will emerge victorious.

- While foreign analysts continued to harp on the question of why American companies couldn’t win in China, Chinese companies were busy building better products. Weibo, a micro-blogging platform initially inspired by Twitter, was far faster to expand multimedia functionality and is now worth more than the American company. Didi, the ride-hailing company that duked it out with Uber, dramatically expanded its product offerings and gives more rides each day in China than Uber does across the entire world. Toutiao, a Chinese news platform often likened to BuzzFeed, uses advanced machine-learning algorithms to tailor its content for each user, boosting its valuation many multiples above the American website. Dismissing these companies as copycats relying on government protection in order to succeed blinds analysts to world-class innovation that is happening elsewhere.

- But the maturation of China’s entrepreneurial ecosystem was about far more than competition with American giants. After companies like Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent had proven how lucrative China’s internet markets could be, new waves of venture capital and talent began to pour into the industry. Markets were heating up, and the number of Chinese startups was growing exponentially. These startups may have taken inspiration from across the ocean, but their real competitors were other domestic companies, and the clashes were taking on all the intensity of a sibling rivalry.

- Battles with Silicon Valley may have created some of China’s homegrown internet Goliaths, but it was cutthroat Chinese domestic competition that forged a generation of gladiator entrepreneurs.

- Zhou embodies the gladiatorial mentality of Chinese internet entrepreneurs. In his world, competition is war and he will stop at nothing to win. In Silicon Valley, his tactics would guarantee social ostracism, antimonopoly investigations, and endless, costly lawsuits. But in the Chinese coliseum, none of these three can hold back combatants. The only recourse when an opponent strikes a low blow is to launch a more damaging counterattack, one that can take the form of copying products, smearing opponents, or even legal detention. Zhou faced all of the above during the “3Q War,” a battle between Zhou’s Qihoo and QQ, the messaging platform of web juggernaut Tencent.

- I witnessed the start of hostilities firsthand one evening in 2010, when Zhou invited me and employees of the newly formed Sinovation Ventures to join his team at a laser tag course outside of Beijing. Zhou was in his element, shooting up the competition, when his cell phone rang. It was an employee with bad news: Tencent had just launched a copycat of Qihoo 360’s antivirus product and was automatically installing it on any computer that used QQ. Tencent was already a powerful company that wielded enormous influence through its QQ user base. This was a direct challenge to Qihoo’s core business, a matter of corporate life or death in Zhou’s mind, as he wrote in his autobiography, Disruptor.

- Over the next two months, Zhou pulled out every dirty and desperate trick he could think of to beat back Tencent. Qihoo first created a popular new “privacy protection” software that issued dire safety warnings every time a Tencent product was opened. The warnings were often not based on any real security vulnerability, but it was an effective smear campaign against the stronger company. Qihoo then released a piece of “security” software that could filter all ads within QQ, effectively killing the product’s main revenue stream. Soon thereafter, Zhou was on his way to work when he got a phone call: over thirty police officers had raided the Qihoo offices and were waiting there to detain Zhou as part of an investigation. Convinced the raid was orchestrated by Tencent, Zhou drove straight to the airport and fled to Hong Kong to formulate his next move.

- Finally, Tencent took the nuclear option: on November 3, 2010, Tencent announced that it would block the use of QQ messaging on any computer that had Qihoo 360, forcing users to choose between the two products. It was the equivalent of Facebook telling users it would block Facebook access for anyone using Google Chrome. The companies were waging total war against each other, with Chinese users’ computers as the battleground. Qihoo appealed to users for a three-day “QQ strike,” and the government finally stepped in to separate the bloodied combatants. Within a week both QQ and Qihoo 360 had returned to normal functioning, but the scars from these kinds of battles lingered with the entrepreneurs and companies.

- Kaixin001 sued its unsavory rival, but the lawsuit couldn’t undo the damage from live combat. In April 2011, eighteen months after the lawsuit was filed, a Beijing court ordered Renren to pay $60,000 to Kaixin001, but the once-promising challenger was now a shadow of its former self. One month after that, Renren went public on the New York Stock Exchange, raising $740 million. (Story about Kaixin001 having the domain Kaixin bought by Renren who then stole all its traffic.)

- The War of a Thousand Groupons crystallized this phenomenon. Soon after its launch in 2008, Groupon became the darling of the American startup world. The premise was simple: offer coupons that worked only if a sufficient number of buyers used them. The buyers got a discount and the sellers got guaranteed bulk sales. It was a hit in post-financial-crisis America, and Groupon’s valuation skyrocketed to over $1 billion in just sixteen months, the fastest pace in history.

- But at the bottom of that dogpile, at the center of this royal rumble, was Wang Xing. In the previous seven years, he had copied three American technology products, built two companies, and sharpened the skills needed to survive in the coliseum. Wang had turned from a geeky engineer who cloned American websites into a serial entrepreneur with a keen sense for technology products, business models, and gladiatorial competition.

- When Meituan launched, the battle was just heating up, with competitors blowing through hundreds of millions of dollars in offline advertising. The going logic went that in order to stand out from the herd, a company had to raise lots of money and spend it to win over customers through advertising and subsidies. That high market share could then be used to raise more money and repeat the cycle. With overeager investors funding thousands of near-identical companies, Chinese urbanites took advantage of the absurd discounts to eat out in droves. It was as if China’s venture-capital community were treating the entire country to dinner.

- But Wang was aware of the dangers of burning cash—that’s how he’d lost Xiaonei, his Facebook copy—and he foresaw the danger of trying to buy long-term customer loyalty with short-term bargains. If you only competed on subsidies, customers would endlessly jump from platform to platform in search of the best deal. Let the competitors spend the money on subsidizing meals and educating the market—he would reap the harvest that they sowed. So Wang focused on keeping costs down while iterating his product. Meituan eschewed all offline advertising, instead pouring resources into tweaking products, bringing down the cost of user acquisition and retention, and optimizing a complex back end. That back end included processing payments coming in from millions of customers and going out to tens of thousands of sellers. It was a daunting engineering challenge for which Wang’s decade of hands-on experience had prepared him.

- One of Meituan’s core differentiations was its relationship with sellers, a crucial piece of the equation often overlooked by startups obsessed with market share. Meituan pioneered an automated payment mechanism that got money into the hands of businesses quicker, a welcome change at a time when group-buying startups were dying by the day, sticking restaurants with unpaid bills. Stability inspired loyalty, and Meituan leveraged it to build out larger networks of exclusive partnerships.

- From the outside, these types of venture-funded battles for market share look to be determined solely by who can raise the most capital and thus outlast their opponents. That’s half-true: while the amount of money raised is important, so is the burn rate and the “stickiness” of the customers bought through subsidies. Startups locked in these battles are almost never profitable at the time, but the company that can drive its losses-per-customer-served to the bare minimum can outlast better-funded competitors. Once the bloodshed is over and prices begin to rise, that same ruthless efficiency will be a major asset on the road to profitability.

- Wang Xing embodied a philosophy of conquest tracing back to the fourteenth-century emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, the leader of a rebel army who outlasted dozens of competing warlords to found the Ming Dynasty: “Build high walls, store up grain, and bide your time before claiming the throne.” For Wang Xing, venture funding was his grain, a superior product was his wall, and a billion-dollar market would be his throne.

- Meituan merged with rival Dianping in late 2015, keeping Wang in charge of the new company. By 2017 the hybrid juggernaut was fielding 20 million different orders a day from a pool of 280 million monthly active users. Most customers had long forgotten that Meituan began as a group-buying site. They knew it for what it had become: a sprawling consumer empire covering noodles, movie tickets, and hotel bookings. Today, Meituan Dianping is valued at $30 billion, making it the fourth most valuable startup in the world, ahead of Airbnb and Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

- Entrepreneurs, Electricity, and Oil

- Wang’s story is about more than just the copycat who made good. His transformation charts the evolution of China’s technology ecosystem, and that ecosystem’s greatest asset: its tenacious entrepreneurs. Those entrepreneurs are beating Silicon Valley juggernauts at their own game and have learned how to survive in the single most competitive startup environment in the world. They then leveraged China’s internet revolution and mobile internet explosion to breathe life into the country’s new consumer-driven economy.

- But to do that they need more than just their own street-smart business sensibilities. If artificial intelligence is the new electricity, big data is the oil that powers the generators. And as China’s vibrant and unique internet ecosystem took off after 2012, it turned into the world’s top producer of this petroleum for the age of artificial intelligence.

- 3. China's Alternate Internet

- As we talked, I could see Guo’s mind working in overdrive. He was absorbing everything and formulating the outlines of a plan. Silicon Valley’s ecosystem had taken shape organically over several decades. But what if we in China could speed up that process by brute-forcing the geographic proximity? We could pick one street in Zhongguancun, clear out all the old inhabitants, and open the space to key players in this kind of ecosystem: VC firms, startups, incubators, and service providers. He already had a name in mind: Chuangye Dajie—Avenue of the Entrepreneurs.

- In my view, that willingness to get one’s hands dirty in the real world separates Chinese technology companies from their Silicon Valley peers. American startups like to stick to what they know: building clean digital platforms that facilitate information exchanges. Those platforms can be used by vendors who do the legwork, but the tech companies tend to stay distant and aloof from these logistical details.

- Silicon Valley juggernauts are amassing data from your activity on their platforms, but that data concentrates heavily in your online behavior, such as searches made, photos uploaded, YouTube videos watched, and posts “liked.” Chinese companies are instead gathering data from the real world: the what, when, and where of physical purchases, meals, makeovers, and transportation. Deep learning can only optimize what it can “see” by way of data, and China’s physically grounded technology ecosystem gives these algorithms many more eyes into the content of our daily lives. As AI begins to “electrify” new industries, China’s embrace of the messy details of the real world will give it an edge on Silicon Valley.

- Simple as that transition sounds, it had profound implications for the particular shape that the Chinese internet would take. Smartphone users not only acted differently than their desktop peers; they also wanted different things. For mobile-first users, the internet wasn’t just an abstract collection of digital information that you accessed from a set location. Rather, the internet was a tool that you brought with you as you moved around cities—it should help solve the local problems you run into when you need to eat, shop, travel, or just get across town. Chinese startups needed to build their products accordingly.

- This opened a real opportunity for Chinese startups backed by Chinese VCs to break new ground in order to foster Chinese-style innovation. At Sinovation, our first round of investment went into incubating nine companies, several of which were eventually acquired or controlled by Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent. Those three Chinese internet juggernauts (collectively known by the abbreviation “BAT”) used our startups to accelerate their transition into mobile internet companies. Those startup acquisitions formed a solid foundation for their mobile efforts, but it would be a secretive in-house project at Tencent that first cracked open the potential of what I call China’s alternate internet universe.

- WeChat: Humble Beginnings, Huge Ambitions

- Jack Ma was less amused. He called the move by Tencent a “Pearl Harbor attack” on Alibaba’s dominance in digital commerce. Alibaba’s Alipay had pioneered digital payments tailored for Chinese users back in 2004 and later adapted the product for smartphones. But overnight WeChat had taken all the momentum in new types of mobile payments, nudging millions of new users into linking their bank accounts to what was already the most powerful social app in China. Ma warned Alibaba employees that if they didn’t fight to hold their grip on mobile payments, it would spell the company’s end. Observers at the time thought this was just typical over-the-top rhetoric from Jack Ma, a charismatic entrepreneur with a genius for rallying his troops. But looking back four years later, it seems likely that Ma saw what was coming.

- China’s mass innovation campaign did that by directly subsidizing Chinese technology entrepreneurs and shifting the cultural zeitgeist. It gave innovators the money and space they needed to work their magic, and it got their parents to finally stop nagging them about taking a job at a local state-owned bank.

- Nine months after Li’s speech, China’s State Council—roughly equivalent to the U.S. president’s cabinet—issued a major directive on advancing mass entrepreneurship and innovation. It called for the creation of thousands of technology incubators, entrepreneurship zones, and government-backed “guiding funds” to attract greater private venture capital. The State Council’s plan promoted preferential tax policies and the streamlining of government permits for starting a business.

- Following the issuance of the State Council directive, cities around China rapidly copied Guo Hong’s vision and rolled out their own versions of the Avenue of the Entrepreneurs. They used tax discounts and rent rebates to attract startups. They created one-stop-shop government offices where entrepreneurs could quickly register their companies. The flood of subsidies created 6,600 new startup incubators around the nation, more than quadrupling the overall total. Suddenly, it was easier than ever for startups to get quality space, and they could do so at discount rates that left more money for building their businesses.

- But if the portfolio companies succeed—say, double in value within five years—then the fund’s manager caps the government’s upside from the fund at a predetermined percentage, perhaps 10 percent, and uses private money to buy the government’s shares out at that rate. That leaves the remaining 90 percent gain on the government’s investment to be distributed among private investors who have already seen their own investments double. Private investors are thus incentivized to follow the government’s lead, investing in funds and industries that the local government wants to foster. During China’s mass innovation push, use of local government guiding funds exploded, nearly quadrupling from $7 billion in 2013 to $27 billion in 2015. (Nearly identical to Israel's scheme in Start-up Nation)

- Now it seemed like any smart and experienced young person with a novel idea and some technical chops could throw together a business plan and find funding to get his or her startup off the ground.

- American policy analysts and investors looked askance at this heavy-handed government intervention in what are supposed to be free and efficient markets. Private-sector players make better bets when it comes to investing, they said, and government-funded innovation zones or incubators will be inefficient, a waste of taxpayer money. In the minds of many Silicon Valley power players, the best thing that the federal government can do is leave them alone.

- But what these critics miss is that this process can be both highly inefficient and extraordinarily effective. When the long-term upside is so monumental, overpaying in the short term can be the right thing to do. The Chinese government wanted to engineer a fundamental shift in the Chinese economy, from manufacturing-led growth to innovation-led growth, and it wanted to do that in a hurry.

- Chinese culture traditionally has a tendency toward conformity and a deference toward authority figures, such as parents, bosses, teachers, and government officials. Before a new industry or activity has received the stamp of approval from authority figures, it’s viewed as inherently risky. But if that industry or activity receives a ringing endorsement from Chinese leadership, people will rush to get a piece of the action. That top-down structure inhibits free-ranging or exploratory innovation, but when the endorsement arrives and the direction is set, all corners of society simultaneously spring into action.

- But it was about more than just the money. Ma had become a national hero, but a very relatable one. Blessed with a goofy charisma, he seems like the boy next door. He didn’t attend an elite university and never learned how to code. He loves to tell crowds that when KFC set up shop in his hometown, he was the only one out of twenty-five applicants to be rejected for a job there. China’s other early internet giants often held Ph.D.s or had Silicon Valley experience in the United States. But Ma’s ascent to rock-star status gave a new meaning to “mass entrepreneurship”—in other words, this was something that anyone from the Chinese masses had a shot at.

- The government endorsement and Ma’s example of internet entrepreneurship were particularly effective at winning over some of the toughest customers: Chinese mothers. In the traditional Chinese mentality, entrepreneurship was still something for people who couldn’t land a real job. The “iron rice bowl” of lifetime employment in a government job remained the ultimate ambition for older generations who had lived through famines. In fact, when I had started Sinovation Ventures in 2009, many young people wanted to join the startups we funded but felt they couldn’t do so because of the steadfast opposition of their parents or spouses. To win these families over, I tried everything I could think of, including taking the parents out to nice dinners, writing them long letters by hand, and even running financial projections of how a startup could pay off. Eventually we were able to build strong teams at Sinovation, but every new recruit in those days was an uphill battle.

- Chinese cities were the perfect laboratory for experimentation. Urban China can be a joy, but it can also be a jungle: crowded, polluted, loud, and less than clean. After a day spent commuting on crammed subways and navigating eight-lane intersections, many middle-class Chinese just want to be spared another trip outdoors to get a meal or run an errand. Lucky for them, these cities are also home to large pools of migrant laborers who would gladly bring that service to their door for a small fee. It’s an environment built for O2O.

- For Chinese people, the transition took the edge off urban life. For small businesses, it meant a boom in customers, as the reductions in friction led Chinese urbanites to spend more. And for China’s new wave of startups, it meant skyrocketing valuations and a ceaseless drive to push into ever more sectors of urban life.

- With the rise of O2O, WeChat had grown into the title bestowed on it by Connie Chan of leading VC fund Andreesen Horowitz: a remote control for our lives. It had become a super-app, a hub for diverse functions that are spread across dozens of different apps in other ecosystems. In effect, WeChat has taken on the functionality of Facebook, iMessage, Uber, Expedia, eVite, Instagram, Skype, PayPal, Grubhub, Amazon, LimeBike, WebMD, and many more. It isn’t a perfect substitute for any one of those apps, but it can perform most of the core functions of each, with frictionless mobile payments already built in.

- In China, companies tend to go “heavy.” They don’t want to just build the platform—they want to recruit each seller, handle the goods, run the delivery team, supply the scooters, repair those scooters, and control the payment. And if need be, they’ll subsidize that entire process to speed user adoption and undercut rivals. To Chinese startups, the deeper they get into the nitty-gritty—and often very expensive—details, the harder it will be for a copycat competitor to mimic the business model and undercut them on price. Going heavy means building walls around your business, insulating yourself from the economic bloodshed of China’s gladiator wars. These companies win both by outsmarting their opponents and by outworking, outhustling, and outspending them on the street.

- Other examples of O2O companies in China going heavy abound. After driving Uber out of the Chinese ride-hailing market, Didi has begun buying up gas stations and auto repair shops to service its fleet, making great margins because of its understanding of its drivers and their trust in the Didi brand. While Airbnb largely remains a lightweight platform for listing your home, the company’s Chinese rival, Tujia, manages a large chunk of rental properties itself. For Chinese hosts, Tujia offers to take care of much of the grunt work: cleaning the apartment after each visit, stocking it with supplies, and installing smart locks.

- In the short run, this cash-flow stimulated the Chinese economy and pumped up valuations. But the long-term legacy of this movement is the data environment it created. By enrolling the vendors, processing the orders, delivering the food, and taking in the payments, China’s O2O champions began amassing a wealth of real-world data on the consumption patterns and personal habits of their users. Going heavy gave these companies a data edge over their Silicon Valley peers, but it was mobile payments that would extend their reach even further into the real world and turn that data edge into a commanding lead.

- During 2015 and 2016, Tencent and Alipay gradually introduced the ability to pay at shops by simply scanning a QR code—basically a square bar code for phones—within the app. It’s a scan-or-get-scanned world. Larger businesses bought simple POS devices that can scan the QR code displayed on customers’ phones and charge them for the purchase. Owners of small shops could just print out a picture of a QR code that was linked to their WeChat Wallet. Customers then use the Alipay or WeChat apps to scan the code and enter the payment total, using a thumbprint for confirmation. Funds are instantly transferred from one bank account to the other—no fees and no need to fumble with wallets. It marked a stark departure from the credit-card model in the developed world. When they were first introduced, credit cards were cutting edge, the most convenient and cost-effective solution to the payment problem. But that advantage has now turned into a liability, with fees of 2.5 to 3 percent on most charges turning into a drag on adoption and utilization.

- China’s mobile payment infrastructure extended its usage far beyond traditional debit cards. Alipay and WeChat even allow peer-to-peer transfers, meaning you can send money to family, friends, small-time merchants, or strangers. Frictionless and hooked into mobile, the apps soon turned into tools for “tipping” the creators of online articles and videos. Micro-payments of as little as fifteen cents flourished. The companies also decided not to charge commissions on the vast majority of transfers, meaning people accepted mobile payments for all transactions—none of the mandatory minimum purchases or fifty-cent fees charged by U.S. retailers on small purchases with credit cards.

- Cash has disappeared so quickly from Chinese cities that it even “disrupted” crime. In March 2017, a pair of Chinese cousins made headlines with a hapless string of robberies. The pair had traveled to Hangzhou, a wealthy city and home to Alibaba, with the goal of making a couple of lucrative scores and then skipping town. Armed with two knives, the cousins robbed three consecutive convenience stores only to find that the owners had almost no cash to hand over—virtually all their customers were now paying directly with their phones. Their crime spree netted them around $125 each—not even enough to cover their travel to and from Hangzhou—when police picked them up. Local media reported rumors that upon arrest one of the brothers cried out, “How is there no cash left in Hangzhou?”

- In the early days of ride-hailing apps in China, riders could book through apps but often paid in cash. A large portion of cars on the leading Chinese platforms were traditional taxis driven by older men—people who weren’t in a rush to give up good old cash. So Tencent offered subsidies to both the rider and the driver if they used WeChat Wallet to pay. The rider paid less and the driver received more, with Tencent making up the difference for both sides. The promotion was extremely costly—due to both legitimate rides and fraudulent ones designed to milk subsidies—but Tencent persisted. That decision paid off. The promotion built up user habits and lured onto the platform taxi drivers, who are the key nodes in the urban consumer economy.

- But that American reluctance to go heavy has slowed adoption of mobile payments and will hurt these companies even more in a data-driven AI world. Data from mobile payments is currently generating the richest maps of consumer activity the world has ever known, far exceeding the data from traditional credit-card purchases or online activity captured by e-commerce players like Amazon or platforms like Google and Yelp. That mobile payment data will prove invaluable in building AI-driven companies in retail, real estate, and a range of other sectors.

- Beijing Bicycle Redux

- While mobile payments totally transformed China’s financial landscape, shared bicycles transformed its urban landscapes. In many ways, the shared bike revolution was turning back the clock. From the time of the Communist Revolution in 1949 through the turn of the millennium, Chinese cities were teeming with bicycles. But as economic reforms created a new middle class, car ownership took off and riding a bicycle became something for individuals who were too poor for four-wheeled transport. Bikes were pushed to the margins of city streets and the cultural mainstream. One woman on the country’s most popular dating show captured the materialism of the moment when she rejected a poor suitor by saying, “I’d rather cry in the back of a BMW than smile on the back of a bicycle.”

- And then, suddenly, China’s alternate universe reversed the tide. Beginning in late 2015, bike-sharing startups Mobike and ofo started supplying tens of millions of internet-connected bicycles and distributing them around major Chinese cities. Mobike outfitted its bikes with QR codes and internet-connected smart locks around the bike’s back wheel. When riders use the Mobike app (or its mini-app in WeChat Wallet) to scan a bike’s QR code, the lock on the back wheel automatically slides open. Mobike users ride the bike anywhere they want and leave it there for the next rider to find. Costs of a ride are based on distance and time, but heavy subsidies mean they often come in at 15 cents or less. It’s a revolutionary, real-world innovation, one made possible by mobile payments. Adding credit-card POS machines to bikes would be too expensive and repair-intensive, but frictionless mobile payments are both cheap to layer onto a bike and incredibly efficient.

- Shared-bike use exploded. In the span of a year, the bikes went from urban oddities to total ubiquity, parked at every intersection, sitting outside every subway exit, and clustered around popular shops and restaurants. It rarely took more than a glance in either direction to find one, and five seconds in the app to unlock it. City streets turned into a rainbow of brightly colored bicycles: orange and silver for Mobike; bright yellow for ofo; and a smattering of blue, green, and red for other copycat companies. By the fall of 2017, Mobike was logging 22 million rides per day, almost all of them in China. That is four times the number of rides Uber was giving each day in 2016, the last time it announced its totals. In the spring of 2018, Mobike was acquired by Wang Xing’s Meituan Dianping for $2.7 billion, just three years after the bike-sharing company’s founding.

- Something new was emerging from all those rides: perhaps the world’s largest and most useful internet-of-things (IoT) networks. The IoT refers to collections of real-world, internet-connected devices that can convey data from the world around them to other devices in the network. Most Mobikes are equipped with solar-powered GPS, accelerators, Bluetooth, and near-field communications capabilities that can be activated by a smartphone. Together, those sensors generate twenty terabytes of data per day and feed it all back into Mobike’s cloud servers.

- Blurred Lines and Brave New Worlds

- In the span of less than two years, China’s bike-sharing revolution has reshaped the country’s urban landscape and deeply enriched its data-scape. This shift forms a dramatic visual illustration of what China’s alternate internet universe does best: solving practical problems by blurring the lines between the online and offline worlds. It takes the core strength of the internet (information transmission) and leverages it in building businesses that reach out into the real world and directly touch on every corner of our lives.

- Building this alternate universe didn’t happen overnight. It required market-driven entrepreneurs, mobile-first users, innovative super-apps, dense cities, cheap labor, mobile payments, and a government-sponsored culture shift. It’s been a messy, expensive, and disruptive process, but the payoff has been tremendous. China has built a roster of technology giants worth over a trillion dollars—a feat accomplished by no other country outside the United States.

- China’s O2O explosion gave its companies tremendous data on the offline lives of their users: the what, where, and when of their meals, massages, and day-to-day activities. Digital payments cracked open the black box of real-world consumer purchases, giving these companies a precise, real-time data map of consumer behavior. Peer-to-peer transactions added a new layer of social data atop those economic transactions. The country’s bike-sharing revolution has carpeted its cities in IoT transportation devices that color in the texture of urban life. They trace tens of millions of commutes, trips to the store, rides home, and first dates, dwarfing companies like Uber and Lyft in both quantity and granularity of data.

- The numbers for these categories lay bare the China-U.S. gap in these key industries. Recent estimates have Chinese companies outstripping U.S. competitors ten to one in quantity of food deliveries and fifty to one in spending on mobile payments. China’s e-commerce purchases are roughly double the U.S. totals, and the gap is only growing. Data on total trips through ride-hailing apps is somewhat scarce, but during the height of competition between Uber and Didi, self-reported numbers from the two companies had Didi’s rides in China at four times the total of Uber’s global rides. When it comes to rides on shared bikes, China is outpacing the United States at an astounding ratio of three hundred to one.

- But building an AI-driven economy requires more than just gladiator entrepreneurs and abundant data. It also takes an army of trained AI engineers and a government eager to embrace the power of this transformative technology. These two factors—AI expertise and government support—are the final pieces of the AI puzzle. When put in place, they will complete our analysis of the competitive balance between the world’s two superpowers in the defining technology of the twenty-first century.

- A Tale of Two Countries

- Those startups are now scrapping for a slice of an AI landscape increasingly dominated by a handful of major players: the so-called Seven Giants of the AI age, which include Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent. These corporate juggernauts are almost evenly split between the United States and China, and they’re making bold plays to dominate the AI economy. They’re using billions of dollars in cash and dizzying stockpiles of data to gobble up available AI talent. They’re also working to construct the “power grids” for the AI age: privately controlled computing networks that distribute machine learning across the economy, with the corporate giants acting as “utilities.” It’s a worrisome phenomenon for those who value an open AI ecosystem and also poses a potential stumbling block to China’s rise as an AI superpower.

- Behind these efforts lies a core difference in American and Chinese political culture: while America’s combative political system aggressively punishes missteps or waste in funding technological upgrades, China’s techno-utilitarian approach rewards proactive investment and adoption. Neither system can claim objective moral superiority, and the United States’ long track record of both personal freedom and technological achievement is unparalleled in the modern era. But I believe that in the age of AI implementation the Chinese approach will have the impact of accelerating deployment, generating more data, and planting the seeds of further growth. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle, one that runs on a peculiar alchemy of digital data, entrepreneurial grit, hard-earned expertise, and political will. To see where the two AI superpowers stand, we must first understand the source of that expertise.

- It was a personal decision (for Enrico Fermi) with earthshaking consequences. After arriving in the United States, Fermi learned of the discovery of nuclear fission by scientists in Nazi Germany and quickly set to work exploring the phenomenon. He created the world’s first self-sustaining nuclear reaction underneath a set of bleachers at the University of Chicago and played an indispensable role in the Manhattan Project. This top-secret project was the largest industrial undertaking the world had ever seen, and it culminated in the development of the world’s first nuclear weapons for the U.S. military. Those bombs put an end to World War II in the Pacific and laid the groundwork for the nuclear world order.

- Fermi and the Manhattan Project embodied an age of discovery that rewarded quality over quantity in expertise. In nuclear physics, the 1930s and 1940s were an age of fundamental breakthroughs, and when it came to making those breakthroughs, one Enrico Fermi was worth thousands of less brilliant physicists. American leadership in this era was built in large part on attracting geniuses like Fermi: men and women who could singlehandedly tip the scales of scientific power.

- But not every technological revolution follows this pattern. Often, once a fundamental breakthrough has been achieved, the center of gravity quickly shifts from a handful of elite researchers to an army of tinkerers—engineers with just enough expertise to apply the technology to different problems. This is particularly true when the payoff of a breakthrough is diffused throughout society rather than concentrated in a few labs or weapons systems.

- Deep-learning pioneers like Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun, and Yoshua Bengio—the Enrico Fermis of AI—continue to push the boundaries of artificial intelligence. And they may yet produce another game-changing breakthrough, one that scrambles the global technological pecking order. But in the meantime, the real action today is with the tinkerers.

- And for this technological revolution, the tinkerers have an added advantage: real-time access to the work of leading pioneers. During the Industrial Revolution, national borders and language barriers meant that new industrial breakthroughs remained bottled up in their country of origin, England. America’s cultural proximity and loose intellectual property laws helped it pilfer some key inventions, but there remained a substantial lag between the innovator and the imitator.

- Not so today. When asked how far China lags behind Silicon Valley in artificial intelligence research, some Chinese entrepreneurs jokingly answer “sixteen hours”—the time difference between California and Beijing. America may be home to the top researchers, but much of their work and insight is instantaneously available to anyone with an internet connection and a grounding in AI fundamentals. Facilitating this knowledge transfer are two defining traits of the AI research community: openness and speed.

- Artificial intelligence researchers tend to be quite open about publishing their algorithms, data, and results. That openness grew out of the common goal of advancing the field and also from the desire for objective metrics in competitions. In many physical sciences, experiments cannot be fully replicated from one lab to the next—minute variations in technique or environment can greatly affect results. But AI experiments are perfectly replicable, and algorithms are directly comparable. They simply require those algorithms to be trained and tested on identical data sets. International competitions frequently pit different computer vision or speech recognition teams against each other, with the competitors opening their work to scrutiny by other researchers.

- On WeChat, China’s AI community coalesces in giant group chats and multimedia platforms to chew over what’s new in AI. Thirteen new media companies have sprung up just to cover the sector, offering industry news, expert analysis, and open-ended dialogue. These AI-focused outlets boast over a million registered users, and half of them have taken on venture funding that values them at more than $10 million each. For more academic discussions, I’m part of the five-hundred-member “Weekly Paper Discussion Group,” just one of the dozens of WeChat groups that come together to dissect a new AI research publication each week. The chat group buzzes with hundreds of messages per day: earnest questions about this week’s paper, screen shots of the members’ latest algorithmic achievements, and, of course, plenty of animated emojis.

- In terms of funding, Google dwarfs even its own government: U.S. federal funding for math and computer science research amounts to less than half of Google’s own R&D budget. That spending spree has bought Alphabet an outsized share of the world’s brightest AI minds. Of the top one hundred AI researchers and engineers, around half are already working for Google.

- Ng left Baidu in 2017 to create his own AI investment fund, but the time he spent at the company both testified to Baidu’s ambitions and strengthened its reputation for research.

- While Google may have jumped off to a massive head start in the arms race for elite AI talent, that by no means guarantees victory. As discussed, fundamental breakthroughs are few and far between, and paradigm-shifting discoveries often emerge from unexpected places. Deep learning came out of a small network of idiosyncratic researchers obsessed with an approach to machine learning that had been dismissed by mainstream researchers. If the next deep learning is out there somewhere, it could be hiding on any number of university campuses or in corporate labs, and there’s no guessing when or where it will show its face. While the world waits for the lottery of scientific discovery to produce a new breakthrough, we remain entrenched in our current era of AI implementation.

- Power Grids Versus AI Batteries

- But the giants aren’t just competing against one another in a race for the next deep learning. They’re also in a more immediate race against the small AI startups that want to use machine learning to revolutionize specific industries. It’s a contest between two approaches to distributing the “electricity” of AI across the economy: the “grid” approach of the Seven Giants versus the “battery” approach of the startups. How that race plays out will determine the nature of the AI business landscape—monopoly, oligopoly, or freewheeling competition among hundreds of companies.

- The “grid” approach is trying to commoditize AI. It aims to turn the power of machine learning into a standardized service that can be purchased by any company—or even be given away for free for academic or personal use—and accessed via cloud computing platforms. In this model, cloud computing platforms act as the grid, performing complex machine-learning optimizations on whatever data problems users require. The companies behind these platforms—Google, Alibaba, and Amazon—act as the utility companies, managing the grid and collecting the fees.

- Hooking into that grid would allow traditional companies with large data sets to easily tap into AI’s optimization powers without having to remake their entire business around it. Google’s TensorFlow, an open-source software ecosystem for building deep learning-models, offers an early version of this but still requires some AI expertise to operate. The goal of the grid approach is to both lower that expertise threshold and increase the functionality of these cloud-based AI platforms. Making use of machine learning is nowhere near as simple as plugging an electric appliance into the wall—and it may never be—but the AI giants hope to push things in that direction and then reap the rewards of generating the “power” and operating the “grid.”

- AI startups are taking the opposite approach. Instead of waiting for this grid to take shape, startups are building highly specific “battery-powered” AI products for each use-case. These startups are banking on depth rather than breadth. Instead of supplying general-purpose machine-learning capabilities, they build new products and train algorithms for specific tasks, including medical diagnosis, mortgage lending, and autonomous drones.

- They are betting that traditional businesses won’t be able to simply plug the nitty-gritty details of their daily operations into an all-purpose grid. Instead of helping those companies access AI, these startups want to disrupt them using AI. They aim to build AI-first companies from the ground up, creating a new roster of industry champions for the AI age.

- A Tale of Two AI Plans

- On October 12, 2016, President Barack Obama’s White House released a long-brewing plan for how the United States can harness the power of artificial intelligence. The document detailed the transformation AI is set to bring to the economy and laid out steps to seize that opportunity: increasing funding for research, stepping up civilian-military cooperation, and making investments to mitigate social disruptions. It offered a decent summary of changes on the horizon and some commonsense prescriptions for adaptation. But the report—issued by the most powerful political office in the United States—had about the same impact as a wonkish policy paper from an academic think tank. Released the same week as Donald Trump’s infamous Access Hollywood videotape, the White House report barely registered in the American news cycle. It did not spark a national surge in interest about AI. It did not lead to a flood of new VC investments and government funding for AI startups. And it didn’t galvanize mayors or governors to adopt AI-friendly policies. In fact, when President Trump took office just three months after the report’s debut, he proposed cutting funding for AI research at the National Science Foundation.

- The limp response to the Obama report made for a stark contrast to the shockwaves generated by the Chinese government’s own AI plan. Like past Chinese government documents on technology, it was plain in its language but momentous in its impact. Published in July 2017, the Chinese State Council’s “Development Plan for a New Generation of Artificial Intelligence” shared many of the same predictions and recommendations as the White House plan. It also spelled out hundreds of industry-specific applications of AI and laid down signposts for China’s progress toward becoming an AI superpower. It called for China to reach the top tier of AI economies by 2020, achieve major new breakthroughs by 2025, and become the global leader in AI by 2030.

- And that is all in just one city. Nanjing’s population of 7 million ranks just tenth in China, a country with a hundred cities of more than a million people. This blizzard of government incentives is going on across many of those cities right now, all competing to attract, fund, and empower AI companies. It’s a process of government-accelerated technological development that I’ve witnessed twice in the past decade. Between 2007 and 2017, China went from having zero high-speed rail lines to having more miles of high-speed rail operational than the rest of the world combined. During the “mass innovation and mass entrepreneurship” campaign that began in 2015, a similar flurry of incentives created 6,600 new startup incubators and shifted the national culture around technology startups.

- Of course, it’s too early to know the exact results of China’s AI campaign, but if Chinese history is any guide, it is likely to be somewhat inefficient but extremely effective. The sheer scope of financing and speed of deployment almost guarantees that there will be inefficiencies. Government bureaucracies cannot rapidly deploy billions of dollars in investments and subsidies without some amount of waste. There will be dorms for AI employees that will never be inhabited, and investments in startups that will never get off the ground. There will be traditional technology companies that merely rebrand themselves as “AI companies” to rake in subsidies, and AI equipment purchases that simply gather dust in government offices.

- Never mind that, on the whole, the loan guarantee program is projected to earn money for the federal government—one high-profile failure was enough to tar the entire enterprise of technological upgrading. (Regarding Obama's stimulus programs for government loan guarantees on promising renewable energy projects and Solyndra as sacrificial lamb.)

- That same divide in political cultures applies to creating a supportive policy environment for AI development. For the past thirty years, Chinese leaders have practiced a kind of techno-utilitarianism, leveraging technological upgrades to maximize broader social good while accepting that there will be downsides for certain individuals or industries. It, like all political structures, is a highly imperfect system. Top-down government mandates to expand investment and production can also send the pendulum of public investment swinging too far in a given direction. In recent years, this has led to massive gluts of supply and unsustainable debt loads in Chinese industries ranging from solar panels to steel. But when national leaders correctly channel those mandates toward new technologies that can lead to seismic economic shifts, the techno-utilitarian approach can have huge upsides.

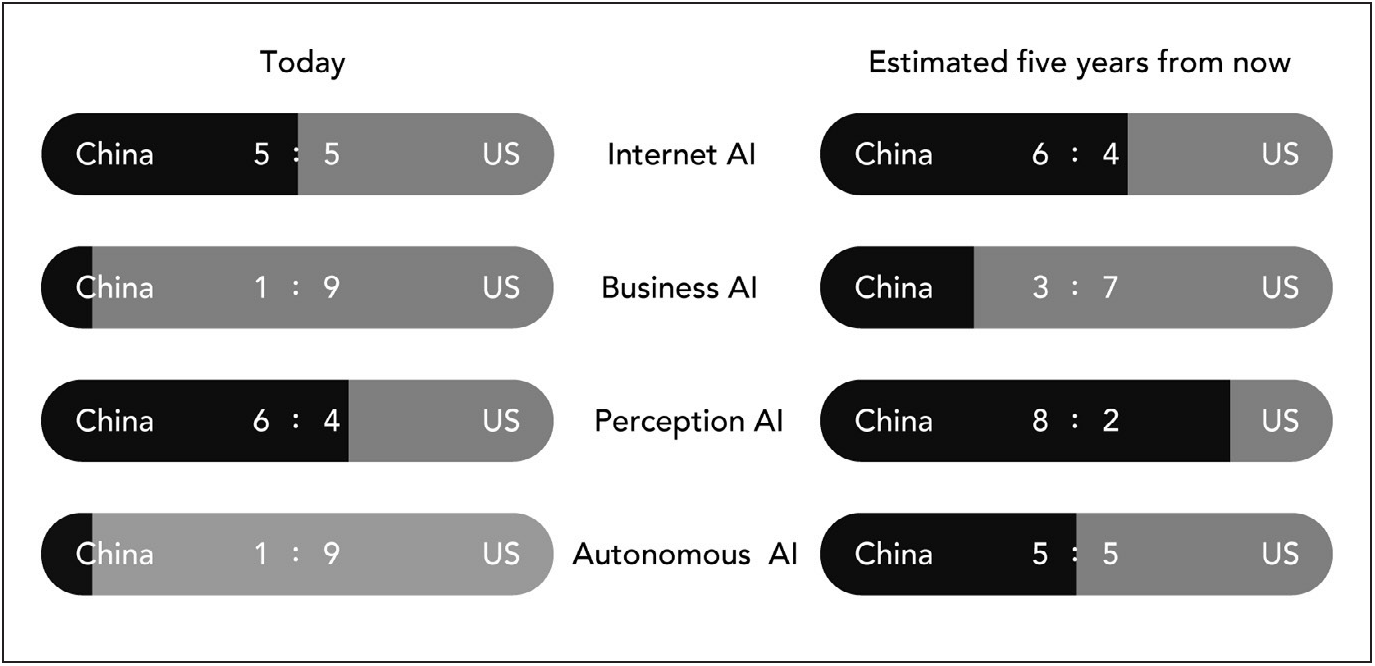

- The Four Waves of AI (Internet, Business, Perception, Autonomous)

- President Trump cannot, of course, speak Chinese. But AI is indeed changing the world, and Chinese companies like iFlyTek are leading the way. By training its algorithms on large data samples of President Trump’s speeches, iFlyTek created a near-perfect digital model of his voice: intonation, pitch, and pattern of speech. It then recalibrated that vocal model for Mandarin Chinese, showing the world what Donald Trump might sound like if he grew up in a village outside Beijing. The movement of lips wasn’t precisely synced to the Chinese words, but it was close enough to fool a casual viewer at first glance. President Obama got the same treatment from iFlyTek: a video of a real press conference but with his professorial style converted to perfect Mandarin.

- Competition, however, won’t play out in just these two countries. AI-driven services that are pioneered in the United States and China will then proliferate across billions of users around the globe, many of them in developing countries. Companies like Uber, Didi, Alibaba, and Amazon are already fiercely competing for these developing markets but adopting very different strategies. While Silicon Valley juggernauts are trying to conquer each new market with their own products, China’s internet companies are instead investing in these countries’ scrappy local startups as they try to fight off U.S. domination. It’s a competition that’s just getting started, and one that will have profound implications for the global economic landscape of the twenty-first century.

- Algorithms are also being used to sniff out “fake news” on the platform, often in the form of bogus medical treatments. Originally, readers discovered and reported misleading stories—essentially, free labeling of that data. Toutiao then used that labeled data to train an algorithm that could identify fake news in the wild. Toutiao even trained a separate algorithm to write fake news stories. It then pitted those two algorithms against each other, competing to fool one another and improving both in the process. This AI-driven approach to content is paying off. By late 2017, Toutiao was already valued at $20 billion and went on to raise a new round of funding that would value it at $30 billion, dwarfing the $1.7 billion valuation for BuzzFeed at the time. For 2018, Toutiao projected revenues between $4.5 and $7.6 billion. And the Chinese company is rapidly working to expand overseas. After trying and failing in 2016 to buy Reddit, the popular U.S. aggregation and discussion site, in 2017 Toutiao snapped up a France-based news aggregator and Musical.ly, a Chinese video lip-syncing app that’s wildly popular with American teens. (Which later would become Tik Tok!!!!)

- These startups sell their services to traditional companies or organizations, offering to let their algorithms loose on existing databases in search of optimizations. They help these companies improve fraud detection, make smarter trades, and uncover inefficiencies in supply chains. Early instances of business AI have clustered heavily in the financial sector because it naturally lends itself to data analysis. The industry runs on well-structured information and has clear metrics that it seeks to optimize.

- This is not so in China. Chinese companies have never truly embraced enterprise software or standardized data storage, instead keeping their books according to their own idiosyncratic systems. Those systems are often not scalable and are difficult to integrate into existing software, making the cleaning and structuring of data a far more taxing process. Poor data also makes the results of AI optimizations less robust. As a matter of business culture, Chinese companies spend far less money on third-party consulting than their American counterparts. Many old-school Chinese businesses are still run more like personal fiefdoms than modern organizations, and outside expertise isn’t considered something worth paying for.

- Both China’s corporate data and its corporate culture make applying second-wave AI to its traditional companies a challenge. But in industries where business AI can leapfrog legacy systems, China is making serious strides. In these instances, China’s relative backwardness in areas like financial services turns into a springboard to cutting-edge AI applications. One of the most promising of these is AI-powered micro-finance.

- What does an applicant’s phone battery have to do with creditworthiness? This is the kind of question that can’t be answered in terms of simple cause and effect. But that’s not a sign of the limitations of AI. It’s a sign of the limitations of our own minds at recognizing correlations hidden within massive streams of data. By training its algorithms on millions of loans—many that got paid back and some that didn’t—Smart Finance has discovered thousands of weak features that are correlated to creditworthiness, even if those correlations can’t be explained in a simple way humans can understand. Those offbeat metrics constitute what Smart Finance founder Ke Jiao calls “a new standard of beauty” for lending, one to replace the crude metrics of income, zip code, and even credit score.

- Growing mountains of data continue to refine these algorithms, allowing the company to scale up and extend credit to groups routinely ignored by China’s traditional banking sector: young people and migrant workers. In late 2017, the company was making more than 2 million loans per month with default rates in the low single digits, a track record that makes traditional brick-and-mortar banks extremely jealous.