…a.k.a. for the philosophy nerds out there: “The Philosophical Dualism of Money.”

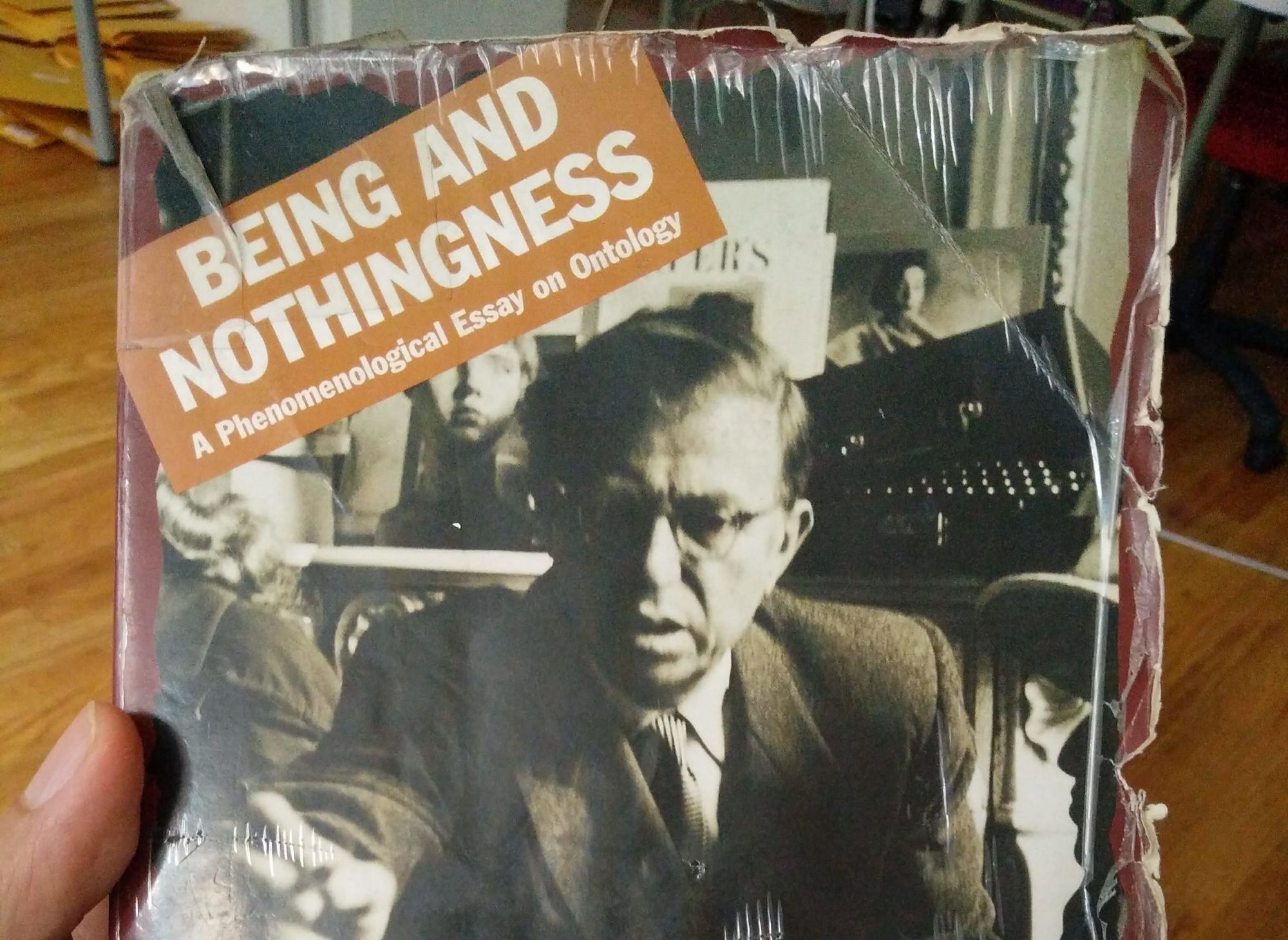

One of my favorite books of all time is Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. Published in 1943, the book is heralded as the landmark text of post-war French existentialism. Several years ago, I discovered the book due to a sparked curiosity from, separately, a friend and professor who both identified as existentialists. Before attempting to read the book, I prepped for the read with a “existential” reading list (Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Dostoevsky, Schopenhauer, Kafka, and Camus) to better my odds of understanding Being and Nothingness (B&N.)

One of the colossal insights I drew from the book is in the first ten pages, where Sartre distills all of philosophy’s most popular dualism debates (love vs. hate, earth vs. heaven, good vs. evil, free will vs. pre-determination, etc.) into one final dualism: the finite vs. the infinite.

Does this mean that by reducing the existent to its manifestations we have succeeded in overcoming all dualisms? It seems rather that we have converted them into a new dualism: that of finite and infinite. Yet the existent in fact can not be reduced to a finite series of manifestations since each one of them is a relation to a subject constantly changing. Although an object may disclose itself only through a single Abschatung, the sole fact of there being a subject implies the possibility of multiplying the points of view on that Abschattung. This suffices to multiply to infinity the Abschattung under consideration. Furthermore if the series of appearances were finite, that would mean that the first appearances do not have the possibility of reappearing, which is absurd, or that they can be all given at once, which is still more absurd. Let us understand indeed that our theory of the phenomenon has replaced the reality of the thing by the objectivity of the phenomenon and that it has based this on an appeal to infinity … Thus the appearance, which is finite, indicates itself in its finitude, but at the same time in order to be grasped as an appearance-of-that-which-appears, it requires that it be surpassed toward infinity.

Keep this passage in mind, because we will be translating its gibberish into something clear, perhaps, even obvious later in this post.

Although dualism and monism are terms normally reserved for philosophy and academia, there’s a great and very practical example we can apply it to: the study of money.

Imagine two philosophers: “Aristodough” and “Payto.” Aristodough argues that a business is worth nothing except the cash it has at present. Payto argues that a business’ true value is in all the verticals and profits it’ll make in the coming few years. Which one would you say is right? Are you only worth your paystub right now, or are you also the value of your future wage growth?

This tension of two seemingly different positions can be described as a dualism. In addition, this dualism clearly demonstrates a core characteristic of money, with the two sides being cash flow and equity. Like reality, seeing either only “what is” or only “what could be” is grasping only half the picture.

Back to our previous question, however, the correct answer between Aristodough and Payto is obviously, both. One can only get a mortgage with cold, hard, presently existing paystubs from W2 employment. At the same time, however, a house’s total worth is only worth both a) what someone will pay for it now, and b) the projections of cash flow it brings.

In other words, if we time-shifted Sartre from his historical context to the present day neo-liberal economy and gave him a edgy name “$ar-trade”, he may argue that cash flow (being) and equity (nothingness) were two sides of the same coin (being-in-itself vs. being-for-itself in relation to reality). If we were to then take the previous passage, and “commercialize” it:

Does this mean that by reducing the company to its balance sheets we have succeeded in overcoming all investor debates about an accurate valuation? It seems rather that we have converted them into a new dualism: that of cash flows and equity. Yet the company in fact can not be reduced to a finite series of cash flows since each one of them is a relation to a company constantly changing. Although a company may disclose itself only through a single cash flow, the sole fact of there being a subject implies the possibility of multiplying the points of view on that cash flow. This suffices to multiply to infinity the cash flow under consideration. Furthermore if the series of cash flows were finite, that would mean that the first cash flow do(es) not have the possibility of reappearing, which is absurd, or that they can be all given at once, which is still more absurd. Let us understand indeed that our theory of the company has replaced the reality of the company (by the objectivity of the company) and that it has based this on an appeal to infinity … Thus the company, which is finite, indicates itself in its finitude, but at the same time in order to be grasped as an appearance-of-that-which-appears, it requires that it be surpassed toward infinity.

For those keeping track, I replaced:

- Dualism => debates about an accurate valuation

- Finite, Infinite (as nouns) => cash flows, equity

- Existent, object, phenomenon=> company

- Abschattung, manifestations, appearances => cash flows

Sartre then subsequently takes a couple hundred pages to explain how he solves this final incarnation of “dualism,” laying the framework for being (the finite) and nothingness (the infinite) into one uniform theory of reality. The ideas in B&N have vast implications, and personally, I have found few books as ambitious and poetic, or as heavy and profound. I do not recommend it for dilettantes or casual reading. I would also recommend few books but it as a cornerstone for making sense of the modern world. As Sartre says, “Life begins on the other side of despair.”

Once one internalizes the ideas of cash flow vs. equity and finite vs. infinite, one will see it everywhere.

In Meg Jay’s book “The Defining Decade,” she writes about twenty-something individuals accumulating career capital to gain access to a higher tier of opportunities, no matter what specifically those opportunities are. Unpaid internships are worthless on paper, but because of their equity in proximity to influential decision makers, they have more prestige than working at a normal hourly job at Starbucks.

Companies often prefer new hires out of an undergraduate program, as opposed to high school students, while the former may lack the same amount of business-specific skills as the latter. In addition, at a professional salary, the value of a new college-grad hire deserves further scrutiny. Why not just hire high school students for a 50% discount (or greater!) and give them a two year apprenticeship?

Among many of the speculative reasons, one is that individuals who have completed a four year undergraduate degree demonstrate an ability to commit to, comply with, and complete a program in an institution for an extended period of time. The specific education doesn’t matter much at all (consulting companies gobble up the top graduates in a variety of majors, outside of business.) Even if a new college grad hire may lack skills at that point, assuming they can stick with the organization, that new hire can become an invaluable candidate for a director or vice president role in a few years.

Parents withstand some of the most grueling work conditions in starting a family e.g. being on call at all hours, uncompensated labor and capital investment for decades, long-term switching costs to starting a new family. Why do we think generations of humans do this year after year? Because in most cases, raising a child is also a disproportionate equity play. There are few investments that will give you back the love, depth, and feeling of connection to any being than raising your own child.

And so we come full circle to Sartre, Being and Nothingness, and finally, to the study of meaning.

If the present feels a little stale, it could mean one did not invest enough into opportunities for meaning (e.g. saying yes to a random job interview from a LinkedIn request,) or that one is forgetting to recognize the future equity play (e.g. a career with a company that is growing rapidly but still small at the moment.) Conversely, if one has an surplus of meaning (sudden reclamation of free time due to completing a messy divorce,) that surplus can be used for present indulgence (enjoying one’s own time and hobbies again) and also for future meaning (re-entering the dating market as a divorcee.)

If reality can be defined as meaning and significance in time (finite vs. infinite,) and money can (sometimes) buy time, then reality can (sometimes) be understood as meaning and significance in relation to personal finance.

Note: Abschattungen — As explained in my Hazel Barnes translation of Being & Nothingess, “used by Sartre in the usual phenomenological sense to refer to the successive appearances of the object ‘in profile.'”