I recently reread Peter Thiel and Blake Master’s Zero to One. This was my second time reading it: first time from the perspective of a builder, this time with the perspective of a funder. Needless to say, the two roles are intertwined: all but the most passive investors will try to find ways to “add value,” and all builders are inherently investors by making decisions on what to build.

With this different perspective, I took away a lot of new nuggets:

1. Seven Questions Every Business Should Answer:

- The Engineering question: Can you create breakthrough technology instead of incremental improvements?

- The Timing question: Is now the right time to start your particular business?

- The monopoly question: Are starting with a big share from a small market?

- The people question: Do you have the right team?

- The distribution question: Do you have a way to deliver your product?

- The durability question: Will your market position be defensible 10 and 20 years into the future?

- The secret question: Have you identified an unique opportunity that others don’t see?

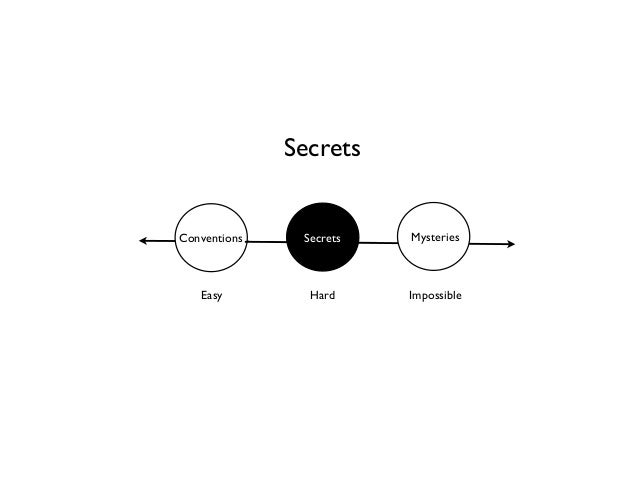

2. Secrets

The best place to look for secrets is where no one else is looking

Two types of secrets: secrets of nature and secrets of people. What secrets is nature not telling you? What secrets are people not telling you?

Example of nutrition where most of the policies were influenced by lobbyist and scientific assessments and discoveries are yet still to be developed.

Tesla knew the secret that people care more about showing off their virtue than actual virtue.

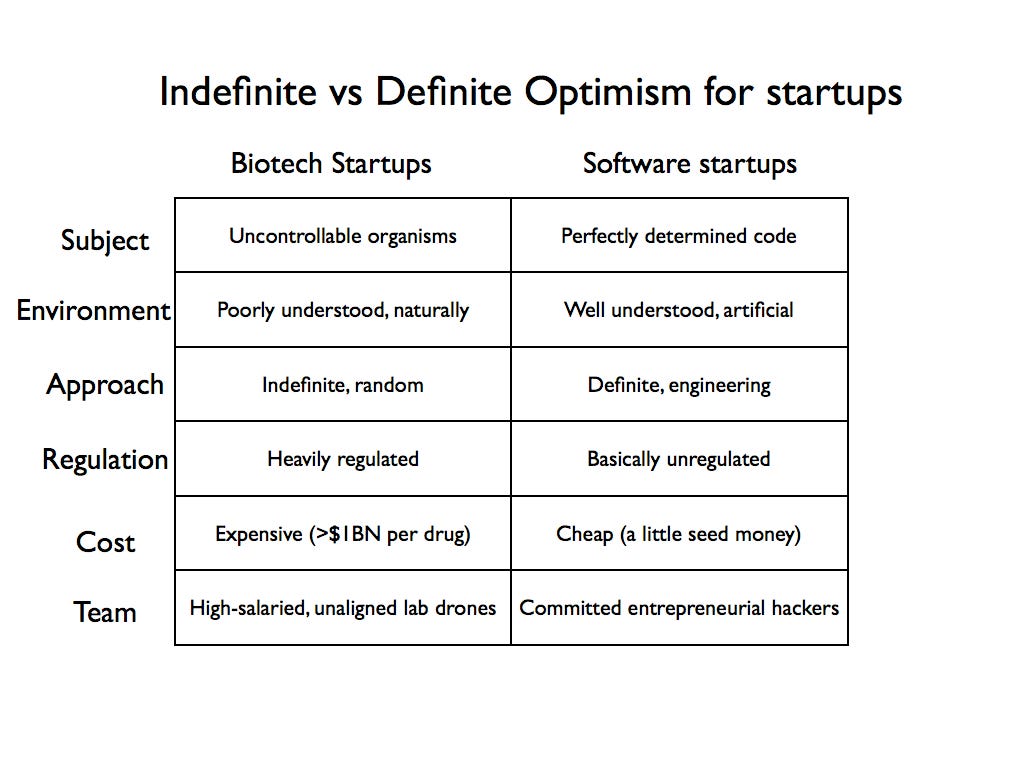

3. The Certainty vs. Outlook Diagram

4. On the audacity of a venture bet

This implies two very strange rules for VCs. First, only invest in companies that have the potential to return the value of the entire fund. This is a scary rule, because it eliminates the vast majority of possible investments. (Even quite successful companies usually succeed on a more humble scale.) This leads to rule number two: because rule number one is so restrictive, there can’t be any other rules.

Consider what happens when you break the first rule. Andreessen Horowitz invested $250,000 in Instagram in 2010. When Facebook bought Instagram just two years later for $1 billion, Andreessen netted $78 million—a 312x return in less than two years. That’s a phenomenal return, befitting the firm’s reputation as one of the Valley’s best. But in a weird way it’s not nearly enough, because Andreessen Horowitz has a $1.5 billion fund: if they only wrote $250,000 checks, they would need to find 19 Instagrams just to break even. This is why investors typically put a lot more money into any company worth funding. (And to be fair, Andreessen would have invested more in Instagram’s later rounds had it not been conflicted out by a previous investment.) VCs must find the handful of companies that will successfully go from 0 to 1 and then back them with every resource.

Of course, no one can know with certainty ex ante which companies will succeed, so even the best VC firms have a “portfolio.” However, every single company in a good venture portfolio must have the potential to succeed at vast scale. At Founders Fund, we focus on five to seven companies in a fund, each of which we think could become a multibillion-dollar business based on its unique fundamentals. Whenever you shift from the substance of a business to the financial question of whether or not it fits into a diversified hedging strategy, venture investing starts to look a lot like buying lottery tickets. And once you think that you’re playing the lottery, you’ve already psychologically prepared yourself to lose.

5. Anna Karenina Principle

All companies are happy in different ways, but miserable in the same. To borrow from Marc Andressen, they failed to find product-market fit.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Karenina_principle

6. What to do with the Power Law (in life and startups):

The power law is not just important to investors; rather, it’s important to everybody because everybody is an investor. An entrepreneur makes a major investment just by spending her time working on a startup. Therefore every entrepreneur must think about whether her company is going to succeed and become valuable. Every individual is unavoidably an investor, too. When you choose a career, you act on your belief that the kind of work you do will be valuable decades from now.

The most common answer to the question of future value is a diversified portfolio: “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket,” everyone has been told. As we said, even the best venture investors have a portfolio, but investors who understand the power law make as few investments as possible. The kind of portfolio thinking embraced by both folk wisdom and financial convention, by contrast, regards diversified betting as a source of strength. The more you dabble, the more you are supposed to have hedged against the uncertainty of the future.

But life is not a portfolio: not for a startup founder, and not for any individual. An entrepreneur cannot “diversify” herself: you cannot run dozens of companies at the same time and then hope that one of them works out well. Less obvious but just as important, an individual cannot diversify his own life by keeping dozens of equally possible careers in ready reserve.

Our schools teach the opposite: institutionalized education traffics in a kind of homogenized, generic knowledge. Everybody who passes through the American school system learns not to think in power law terms. Every high school course period lasts 45 minutes whatever the subject. Every student proceeds at a similar pace. At college, model students obsessively hedge their futures by assembling a suite of exotic and minor skills. Every university believes in “excellence,” and hundred-page course catalogs arranged alphabetically according to arbitrary departments of knowledge seem designed to reassure you that “it doesn’t matter what you do, as long as you do it well.” That is completely false. It does matter what you do. You should focus relentlessly on something you’re good at doing, but before that you must think hard about whether it will be valuable in the future.

For the startup world, this means you should not necessarily start your own company, even if you are extraordinarily talented. If anything, too many people are starting their own companies today. People who understand the power law will hesitate more than others when it comes to founding a new venture: they know how tremendously successful they could become by joining the very best company while it’s growing fast. The power law means that differences between companies will dwarf the differences in roles inside companies. You could have 100% of the equity if you fully fund your own venture, but if it fails you’ll have 100% of nothing. Owning just 0.01% of Google, by contrast, is incredibly valuable (more than $35 million as of this writing).

If you do start your own company, you must remember the power law to operate it well. The most important things are singular: One market will probably be better than all others, as we discussed in Chapter 5. One distribution strategy usually dominates all others, too—for that see Chapter 11. Time and decision-making themselves follow a power law, and some moments matter far more than others—see Chapter 9. However, you can’t trust a world that denies the power law to accurately frame your decisions for you, so what’s most important is rarely obvious. It might even be secret. But in a power law world, you can’t afford not to think hard about where your actions will fall on the curve.

7. Taking Down Malcolm Gladwell and Why One’s Life is not a Lottery Ticket

The most contentious question in business is whether success comes from luck or skill.

What do successful people say? Malcolm Gladwell, a successful author who writes about successful people, declares in Outliers that success results from a “patchwork of lucky breaks and arbitrary advantages.” Warren Buffett famously considers himself a “member of the lucky sperm club” and a winner of the “ovarian lottery.” Jeff Bezos attributes Amazon’s success to an “incredible planetary alignment” and jokes that it was “half luck, half good timing, and the rest brains.” Bill Gates even goes so far as to claim that he “was lucky to be born with certain skills,” though it’s not clear whether that’s actually possible.

Perhaps these guys are being strategically humble. However, the phenomenon of serial entrepreneurship would seem to call into question our tendency to explain success as the product of chance. Hundreds of people have started multiple multimillion-dollar businesses. A few, like Steve Jobs, Jack Dorsey, and Elon Musk, have created several multi-dollar companies. If success were mostly a matter of luck, these kinds of serial entrepreneurs probably wouldn’t exist.

…From the Renaissance and the Enlightenment to the mid-20th century, luck was something to be mastered, dominated, and controlled; everyone agreed that you should do what you could, not focus on what you couldn’t.

Ralph Waldo Emerson captured this ethos when he wrote: “Shallow men believe in luck, believe in circumstances.… Strong men believe in cause and effect.” In 1912, after he became the first explorer to reach the South Pole, Roald Amundsen wrote: “Victory awaits him who has everything in order—luck, people call it.” No one pretended that misfortune didn’t exist, but prior generations believed in making their own luck by working hard.

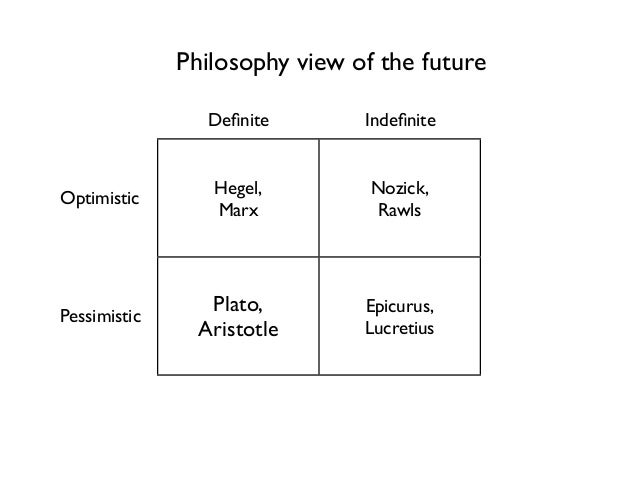

CAN YOU CONTROL YOUR FUTURE?

You can expect the future to take a definite form or you can treat it as hazily uncertain. If you treat the future as something definite, it makes sense to understand it in advance and to work to shape it. But if you expect an indefinite future ruled by randomness, you’ll give up on trying to master it.

Indefinite attitudes to the future explain what’s most dysfunctional in our world today. Process trumps substance: when people lack concrete plans to carry out, they use formal rules to assemble a portfolio of various options. This describes Americans today. In middle school, we’re encouraged to start hoarding “extracurricular activities.” In high school, ambitious students compete even harder to appear omnicompetent. By the time a student gets to college, he’s spent a decade curating a bewilderingly diverse résumé to prepare for a completely unknowable future. Come what may, he’s ready—for nothing in particular.

A definite view, by contrast, favors firm convictions. Instead of pursuing many-sided mediocrity and calling it “well-roundedness,” a definite person determines the one best thing to do and then does it. Instead of working tirelessly to make herself indistinguishable, she strives to be great at something substantive—to be a monopoly of one. This is not what young people do today, because everyone around them has long since lost faith in a definite world. No one gets into Stanford by excelling at just one thing, unless that thing happens to involve throwing or catching a leather ball.

You can also expect the future to be either better or worse than the present. Optimists welcome the future; pessimists fear it.

INDEFINITE OPTIMISM

After a brief pessimistic phase in the 1970s, indefinite optimism has dominated American thinking ever since 1982, when a long bull market began and finance eclipsed engineering as the way to approach the future. To an indefinite optimist the future will be better, but he doesn’t know how exactly, so he won’t make any specific plans. He expects to profit from the future but sees no reason to design it concretely.

Instead of working for years to build a new product, indefinite optimists rearrange already-invented ones. Bankers make money by rearranging the capital structures of already existing companies. Lawyers resolve disputes over old things or help other people structure their affairs. And private equity investors and management consultants don’t start new businesses; they squeeze extra efficiency from old ones with incessant procedural optimizations. It’s no surprise that these fields all attract disproportionate numbers of high-achieving Ivy League optionality chasers; what could be a more appropriate reward for two decades of résumé-building than a seemingly elite, process-oriented career that promises to “keep options open”?

Recent graduates’ parents often cheer them on the established path. The strange history of the Baby Boom produced a generation of indefinite optimists so used to effortless progress that they feel entitled to it. Whether you were born in 1945 or 1950 or 1955, things got better every year for the first 18 years of your life, and it had nothing to do with you. Technological advance seemed to accelerate automatically, so the Boomers grew up with great expectations but few specific plans for how to fulfill them. Then, when technological progress stalled in the 1970s, increasing income inequality came to the rescue of the most elite Boomers. Every year of adulthood continued to get automatically better and better for the rich and successful. The rest of their generation was left behind, but the wealthy Boomers who shape public opinion today see little reason to question their naïve optimism. Since tracked careers worked for them, they can’t imagine that they won’t work for their kids, too.

Malcolm Gladwell says you can’t understand Bill Gates’s success without understanding his fortunate personal context: he grew up in a good family, went to a private school equipped with a computer lab, and counted Paul Allen as a childhood friend. But perhaps you can’t understand Malcolm Gladwell without understanding his historical context as a Boomer (born in 1963). When Baby Boomers grow up and write books to explain why one or another individual is successful, they point to the power of a particular individual’s context as determined by chance. But they miss the even bigger social context for their own preferred explanations: a whole generation learned from childhood to overrate the power of chance and underrate the importance of planning. Gladwell at first appears to be making a contrarian critique of the myth of the self-made businessman, but actually his own account encapsulates the conventional view of a generation.

…We have to find our way back to a definite future, and the Western world needs nothing short of a cultural revolution to do it.

Where to start? John Rawls will need to be displaced in philosophy departments. Malcolm Gladwell must be persuaded to change his theories. And pollsters have to be driven from politics. But the philosophy professors and the Gladwells of the world are set in their ways, to say nothing of our politicians. It’s extremely hard to make changes in those crowded fields, even with brains and good intentions.

A startup is the largest endeavor over which you can have definite mastery. You can have agency not just over your own life, but over a small and important part of the world. It begins by rejecting the unjust tyranny of Chance. You are not a lottery ticket.

8. The opposite of the lean startup movement is…

1. It is better to risk boldness than triviality.

2. A bad plan is better than no plan.

3. Competitive markets destroy profits.

4. Sales matters just as much as product.

9. Rules for Monopoly Building

Thiel describes companies that bring in large cash flows in their future as sharing the following characteristics:

- Proprietary technology: it’s hard or impossible to replicate your product(e.g. Google’s search algorithms); aim for 10x better any substitute in some key aspects

- Network effects: your product becomes increasingly useful as more people use it (e.g. Facebook)

- Economies of scale: a business gets stronger as it gets bigger; the marginal cost of producing an extra unit is negligible (e.g. Software startups)

- Branding: creating a strong and powerful brand is the best way to grow a monopoly (e.g. Apple)

To achieve growth and create a monopoly:

- Start small and monopolize: it’s always a red flag when entrepreneurs talk about getting 1% of a $100 billion market. In practice, a large market will either lack a good starting point or it will be open to competition, so it’s hard to ever reach that 1%. And even if you do succeed in gaining a small foothold, you’ll have to be satisfied with keeping the lights on: cutthroat competition means your profits will be zero. Once you create and dominate a niche market, then you should gradually expand into related and slightly broader markets

- Scale up: once you dominate a niche market expand to adjacent markets (e.g. Amazon and eBay)

- Don’t disrupt: directly challenging large competitors will totally reduce your profits (e.g. Napster vs U.S. recording industry)

10. “Brilliant thinking is rare, but courage is in even shorter supply than genius.”

Basically Thiel’s version of:

- Action and execution is more in scarcity than vision

- 知易行难 — 孙中山

- The efficient market hypothesis is null for entrepreneurship

(Out)source(s):

- https://medium.com/@Stefania_druga/zero-to-one-my-summary-of-peter-thiel-s-book-bbb1e3676457

- https://www.slideshare.net/drugastefania/zero-to-one-46976933

- https://productivityist.com/book-review-zero-to-one/

- https://fs.blog/2014/09/peter-thiel-zero-to-one/

- http://www.dansilvestre.com/zero-one-peter-thiel/

- https://www.meaningfulhq.com/zero-to-one-by-peter-thiel.html

- http://blakemasters.com/peter-thiels-cs183-startup